River Blindness on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness, is a disease caused by infection with the

The phenomenon is so common when DEC is used that this drug is the basis of a skin patch test used to confirm that diagnosis. The drug patch is placed on the skin, and if the patient is infected with ''O. volvulus'' microfilaria, localized

The phenomenon is so common when DEC is used that this drug is the basis of a skin patch test used to confirm that diagnosis. The drug patch is placed on the skin, and if the patient is infected with ''O. volvulus'' microfilaria, localized

In mass drug administration (MDA) programmes, the treatment for onchocerciasis is

In mass drug administration (MDA) programmes, the treatment for onchocerciasis is

About 21 million people were infected with this

About 21 million people were infected with this

NCT00790998

. (editorial) A

CDC Parasites of public health concern

{{Authority control Spirurida Tropical diseases Helminthiases Infectious diseases with eradication efforts Parasitic infestations, stings, and bites of the skin Wikipedia medicine articles ready to translate Wikipedia infectious disease articles ready to translate

parasitic worm

Parasitic worms, also known as helminths, are large macroparasites; adults can generally be seen with the naked eye. Many are intestinal worms that are soil-transmitted and infect the gastrointestinal tract. Other parasitic worms such as sc ...

''Onchocerca volvulus

''Onchocerca volvulus'' is a filarial (arthropod-borne) nematode (roundworm) that causes onchocerciasis (river blindness), and is the second-leading cause of blindness due to infection worldwide after trachoma. It is one of the 20 neglected trop ...

''. Symptoms include severe itching, bumps under the skin, and blindness

Visual impairment, also known as vision impairment, is a medical definition primarily measured based on an individual's better eye visual acuity; in the absence of treatment such as correctable eyewear, assistive devices, and medical treatmentâ ...

. It is the second-most common cause of blindness due to infection, after trachoma

Trachoma is an infectious disease caused by bacterium ''Chlamydia trachomatis''. The infection causes a roughening of the inner surface of the eyelids. This roughening can lead to pain in the eyes, breakdown of the outer surface or cornea of ...

.

The parasite worm is spread by the bites of a black fly

A black fly or blackfly (sometimes called a buffalo gnat, turkey gnat, or white socks) is any member of the family Simuliidae of the Culicomorpha infraorder. It is related to the Ceratopogonidae, Chironomidae, and Thaumaleidae. Over 2,200 spec ...

of the ''Simulium

''Simulium'' is a genus of black flies, which may transmit diseases such as onchocerciasis (river blindness). It is a large genus with several hundred species, and 41 subgenera.

The flies are pool feeders. Their saliva, which contains antico ...

'' type. Usually, many bites are required before infection occurs. These flies live near rivers, hence the common name of the disease. Once inside a person, the worms create larvae

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

The ...

that make their way out to the skin, where they can infect the next black fly that bites the person. There are a number of ways to make the diagnosis, including: placing a biopsy

A biopsy is a medical test commonly performed by a surgeon, interventional radiologist, or an interventional cardiologist. The process involves extraction of sample cells or tissues for examination to determine the presence or extent of a diseas ...

of the skin in normal saline

Saline (also known as saline solution) is a mixture of sodium chloride (salt) and water. It has a number of uses in medicine including cleaning wounds, removal and storage of contact lenses, and help with dry eyes. By injection into a vein it ...

and watching for the larva to come out; looking in the eye for larvae; and looking within the bumps under the skin for adult worms.

A vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifie ...

against the disease does not exist. Prevention is by avoiding being bitten by flies. This may include the use of insect repellent

An insect repellent (also commonly called "bug spray") is a substance applied to skin, clothing, or other surfaces to discourage insects (and arthropods in general) from landing or climbing on that surface. Insect repellents help prevent and cont ...

and proper clothing. Other efforts include those to decrease the fly population by spraying insecticide

Insecticides are substances used to kill insects. They include ovicides and larvicides used against insect eggs and larvae, respectively. Insecticides are used in agriculture, medicine, industry and by consumers. Insecticides are claimed to b ...

s. Efforts to eradicate the disease by treating entire groups of people twice a year are ongoing in a number of areas of the world. Treatment of those infected is with the medication ivermectin

Ivermectin (, '' EYE-vÉr-MEK-tin'') is an antiparasitic drug. After its discovery in 1975, its first uses were in veterinary medicine to prevent and treat heartworm and acariasis. Approved for human use in 1987, today it is used to treat inf ...

every six to twelve months. This treatment kills the larvae but not the adult worms. The antibiotic doxycycline

Doxycycline is a broad-spectrum tetracycline class antibiotic used in the treatment of infections caused by bacteria and certain parasites. It is used to treat bacterial pneumonia, acne, chlamydia infections, Lyme disease, cholera, typhus, an ...

weakens the worms by killing an associated Associated may refer to:

*Associated, former name of Avon, Contra Costa County, California

* Associated Hebrew Schools of Toronto, a school in Canada

*Associated Newspapers, former name of DMG Media, a British publishing company

See also

*Associati ...

bacterium called ''Wolbachia

''Wolbachia'' is a genus of intracellular bacteria that infects mainly arthropod species, including a high proportion of insects, and also some nematodes. It is one of the most common parasitic microbes, and is possibly the most common reproduct ...

'', and is recommended by some as well. The lumps under the skin may also be removed by surgery.

About 15.5 million people are infected with river blindness. Approximately 0.8 million have some amount of loss of vision from the infection. Most infections occur in sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

, although cases have also been reported in Yemen

Yemen (; ar, Ù±ÙÙÙÙÙ

ÙÙ, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi ArabiaâYemen border, north and ...

and isolated areas of Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

and South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

. In 1915, the physician Rodolfo Robles

Rodolfo Robles (1878â1939) was a Guatemalan physician and philanthropist. In 1915, he was the first to describe onchocerciasis in Latin America, which was known and widespread on the African continent and first described in 1890 by Sir Patr ...

first linked the worm to eye disease. It is listed by the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of h ...

(WHO) as a neglected tropical disease

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a diverse group of tropical disease, tropical infections that are common in low-income populations in Developing country, developing regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. They are caused by a variety ...

. In 2013 Colombia became first country to eradicate this disease.

Signs and symptoms

Adult worms remain in subcutaneous nodules, limiting access to the host's immune system.Microfilaria

::''Microfilaria may also refer to an informal "collective group" genus name, proposed by Cobbold in 1882. While a convenient category for newly discovered microfilariae which can not be assigned to a known species because the adults are unknown, ...

e, in contrast, are able to induce intense inflammatory responses, especially upon their death. ''Wolbachia

''Wolbachia'' is a genus of intracellular bacteria that infects mainly arthropod species, including a high proportion of insects, and also some nematodes. It is one of the most common parasitic microbes, and is possibly the most common reproduct ...

'' species have been found to be endosymbiont

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: á¼Î½Î´Î¿Î½ ''endon'' "within" ...

s of ''O. volvulus'' adults and microfilariae, and are thought to be the driving force behind most of ''O. volvulus'' morbidity. Dying microfilariae have been recently discovered to release ''Wolbachia'' surface protein that activates TLR2

Toll-like receptor 2 also known as TLR2 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''TLR2'' gene. TLR2 has also been designated as CD282 (cluster of differentiation 282). TLR2 is one of the toll-like receptors and plays a role in the immune sys ...

and TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''TLR4'' gene. TLR4 is a transmembrane protein, member of the toll-like receptor family, which belongs to the pattern recognition receptor (PRR) family. Its activation leads to an ...

, triggering innate immune responses and producing the inflammation and its associated morbidity. The severity of illness is directly proportional to the number of infected microfilariae and the power of the resultant inflammatory response.

Skin involvement typically consists of intense itching, swelling, and inflammation. A grading system has been developed to categorize the degree of skin involvement:

* Acute papular onchodermatitis â scattered pruritic papule

A papule is a small, well-defined bump in the skin. It may have a rounded, pointed or flat top, and may have a dip. It can appear with a stalk, be thread-like or look warty. It can be soft or firm and its surface may be rough or smooth. Some h ...

s

* Chronic papular onchodermatitis â larger papules, resulting in hyperpigmentation

* Lichenified onchodermatitis â hyperpigmented papules

A papule is a small, well-defined bump in the skin. It may have a rounded, pointed or flat top, and may have a dip. It can appear with a stalk, be thread-like or look warty. It can be soft or firm and its surface may be rough or smooth. Some h ...

and plaques, with edema

Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy, hydropsy and swelling, is the build-up of fluid in the body's Tissue (biology), tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin which feels t ...

, lymphadenopathy

Lymphadenopathy or adenopathy is a disease of the lymph nodes, in which they are abnormal in size or consistency. Lymphadenopathy of an inflammatory type (the most common type) is lymphadenitis, producing swollen or enlarged lymph nodes. In cli ...

, pruritus and common secondary bacterial infections

* Skin atrophy â loss of elasticity, the skin resembles tissue paper, 'lizard skin' appearance

* Depigmentation â 'leopard skin' appearance, usually on anterior lower leg

* Glaucoma effect â eyes malfunction, begin to see shadows or nothing

Ocular involvement provides the common name associated with onchocerciasis, river blindness, and may involve any part of the eye from conjunctiva and cornea to uvea

The uvea (; Lat. ''uva'', "grape"), also called the ''uveal layer'', ''uveal coat'', ''uveal tract'', ''vascular tunic'' or ''vascular layer'' is the pigmented middle of the three concentric layers that make up an eye.

History and etymolog ...

and posterior segment, including the retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

and optic nerve

In neuroanatomy, the optic nerve, also known as the second cranial nerve, cranial nerve II, or simply CN II, is a paired cranial nerve that transmits visual system, visual information from the retina to the brain. In humans, the optic nerve i ...

. The microfilariae migrate to the surface of the cornea

The cornea is the transparent front part of the eye that covers the iris, pupil, and anterior chamber. Along with the anterior chamber and lens, the cornea refracts light, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the eye's total optical power ...

. Punctate keratitis

Keratitis is a condition in which the eye's cornea, the clear dome on the front surface of the eye, becomes inflamed. The condition is often marked by moderate to intense pain and usually involves any of the following symptoms: pain, impaired e ...

occurs in the infected area. This clears up as the inflammation subsides. However, if the infection is chronic, sclerosing keratitis can occur, making the affected area become opaque

Opacity or opaque may refer to:

* Impediments to (especially, visible) light:

** Opacities, absorption coefficients

** Opacity (optics), property or degree of blocking the transmission of light

* Metaphors derived from literal optics:

** In lingu ...

. Over time, the entire cornea may become opaque, thus leading to blindness. Some evidence suggests the effect on the cornea is caused by an immune response to bacteria present in the worms.

The infected person's skin is itchy, with severe rashes permanently damaging patches of skin.

Mazzotti reaction

The Mazzotti reaction, first described in 1948, is a symptom complex seen in patients after undergoing treatment of onchocerciasis with the medicationdiethylcarbamazine

Diethylcarbamazine is a medication used in the treatment of filariasis including lymphatic filariasis, tropical pulmonary eosinophilia, and loiasis. It may also be used for prevention of loiasis in those at high risk. While it has been used for o ...

(DEC). Mazzotti reactions can be life-threatening, and are characterized by fever

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a body temperature, temperature above the human body temperature, normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, set point. There is not a single ...

, urticaria

Hives, also known as urticaria, is a kind of skin rash with red, raised, itchy bumps. Hives may burn or sting. The patches of rash may appear on different body parts, with variable duration from minutes to days, and does not leave any long-lasti ...

, swollen and tender lymph nodes, tachycardia

Tachycardia, also called tachyarrhythmia, is a heart rate that exceeds the normal resting rate. In general, a resting heart rate over 100 beats per minute is accepted as tachycardia in adults. Heart rates above the resting rate may be normal (su ...

, hypotension

Hypotension is low blood pressure. Blood pressure is the force of blood pushing against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps out blood. Blood pressure is indicated by two numbers, the systolic blood pressure (the top number) and the dias ...

, arthralgias

Arthralgia (from Greek ''arthro-'', joint + ''-algos'', pain) literally means ''joint pain''. Specifically, arthralgia is a symptom of injury, infection, illness (in particular arthritis), or an allergic reaction to medication.

According to MeSH, ...

, oedema

Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy, hydropsy and swelling, is the build-up of fluid in the body's tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin which feels tight, the area ma ...

, and abdominal pain

Abdominal pain, also known as a stomach ache, is a symptom

Signs and symptoms are the observed or detectable signs, and experienced symptoms of an illness, injury, or condition. A sign for example may be a higher or lower temperature than ...

that occur within seven days of treatment of microfilariasis.

The phenomenon is so common when DEC is used that this drug is the basis of a skin patch test used to confirm that diagnosis. The drug patch is placed on the skin, and if the patient is infected with ''O. volvulus'' microfilaria, localized

The phenomenon is so common when DEC is used that this drug is the basis of a skin patch test used to confirm that diagnosis. The drug patch is placed on the skin, and if the patient is infected with ''O. volvulus'' microfilaria, localized pruritus

Itch (also known as pruritus) is a sensation that causes the desire or reflex to scratch. Itch has resisted many attempts to be classified as any one type of sensory experience. Itch has many similarities to pain, and while both are unpleasant ...

and urticaria are seen at the application site.

Nodding disease

This is an unusual form of epidemic epilepsy associated with onchocerciasis although definitive link has not been established. This syndrome was first described inTanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

by Louise Jilek-Aall, a Norwegian psychiatric doctor in Tanzanian practice, during the 1960s. It occurs most commonly in Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territor ...

and South Sudan

South Sudan (; din, Paguot Thudän), officially the Republic of South Sudan ( din, PaankÉc Cuëny Thudän), is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered by Ethiopia, Sudan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the C ...

. It manifests itself in previously healthy 5â15-year-old children, is often triggered by eating or low temperatures and is accompanied by cognitive impairment. Seizures occur frequently and may be difficult to control. The electroencephalogram

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a method to record an electrogram of the spontaneous electrical activity of the brain. The biosignals detected by EEG have been shown to represent the postsynaptic potentials of pyramidal neurons in the neocortex ...

is abnormal but cerebrospinal fluid

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, colorless body fluid found within the tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord of all vertebrates.

CSF is produced by specialised ependymal cells in the choroid plexus of the ventricles of the bra ...

(CSF) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are normal or show non-specific changes. If there are abnormalities on the MRI they are usually present in the hippocampus

The hippocampus (via Latin from Greek , 'seahorse') is a major component of the brain of humans and other vertebrates. Humans and other mammals have two hippocampi, one in each side of the brain. The hippocampus is part of the limbic system, a ...

. Polymerase chain reaction testing of the CSF does not show the presence of the parasite.

Cause

The cause is ''Onchocerca volvulus

''Onchocerca volvulus'' is a filarial (arthropod-borne) nematode (roundworm) that causes onchocerciasis (river blindness), and is the second-leading cause of blindness due to infection worldwide after trachoma. It is one of the 20 neglected trop ...

''.

Life cycle

The life of the parasite can be traced through the black fly and the human hosts in the following steps: # A ''Simulium'' female black fly takes a blood meal on an infected human host, and ingests microfilaria. # The microfilaria enter the gut and thoracic flight muscles of the black fly, progressing into the first larval stage (J1.). # The larvae mature into the second larval stage (J2.), and move to the proboscis and into the saliva in its third larval stage (J3.). Maturation takes about seven days. # The black fly takes another blood meal, passing the larvae into the next human host's blood. # The larvae migrate to the subcutaneous tissue and undergo two more molts. They form nodules as they mature into adult worms over six to 12 months. # After maturing, adult male worms mate with female worms in the subcutaneous tissue to produce between 700 and 1,500 microfilaria per day. # The microfilaria migrate to the skin during the day, and the black flies only feed in the day, so the parasite is in a prime position for the female fly to ingest it. Black flies take blood meals to ingest these microfilaria to restart the cycle.Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be made by skin biopsy (with or without PCR) or antibody testing.A skin biopsy removes approximately 2 mg of skin tissue by sclerocorneal biospy punch or shaving a cone of skin with a scalpel. The skin tissue sample is analyzed for the parasite larvae using a microscope. Nodulectomy can be used to analyze skin nodules for the presence of parasites. Slit lamp eye exams are used to identify signs of the parasites in and around the eyes of patients whose eyes are effected. Antibody tests when available can aid in the diagnosis of Onchocerciasis.Classification

Onchocerciasis causes different kinds of skin changes, which vary in different geographic regions; it may be divided into the following phases or types: ;''Erisipela de la costa'' :An acute phase, it is characterized by swelling of the face, witherythema

Erythema (from the Greek , meaning red) is redness of the skin or mucous membranes, caused by hyperemia (increased blood flow) in superficial capillaries. It occurs with any skin injury, infection, or inflammation. Examples of erythema not assoc ...

and itching

Itch (also known as pruritus) is a sensation that causes the desire or reflex to scratch. Itch has resisted many attempts to be classified as any one type of sensory experience. Itch has many similarities to pain, and while both are unpleasan ...

. This skin change, ''erisÃpela de la costa'', of acute onchocerciasis is most commonly seen among victims in Central and South America.

;''Mal morando''

:This cutaneous condition is characterized by inflammation

Inflammation (from la, wikt:en:inflammatio#Latin, inflammatio) is part of the complex biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or Irritation, irritants, and is a protective response involving im ...

accompanied by hyperpigmentation

Hyperpigmentation is the darkening of an area of skin or nails caused by increased melanin.

Causes

Hyperpigmentation can be caused by sun damage, inflammation, or other skin injuries, including those related to acne vulgaris.James, William; Ber ...

.

;''Sowda''

:A cutaneous condition, it is a localized type of onchocerciasis.

Additionally, the various skin changes associated with onchocerciasis may be described as follows:

;Leopard skin

:The spotted depigmentation

Depigmentation is the lightening of the skin or loss of pigment. Depigmentation of the skin can be caused by a number of local and systemic conditions. The pigment loss can be partial (injury to the skin) or complete (caused by vitiligo). It can be ...

of the skin that may occur with onchocerciasis

;Elephant skin

:The thickening of human skin that may be associated with onchocerciasis

;Lizard skin

:The thickened, wrinkled skin changes that may result with onchocerciasis

Prevention

Various control programs aim to stop onchocerciasis from being apublic health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

problem. The first was the Onchocerciasis Control Programme (OCP), which was launched in 1974, and at its peak, covered 30 million people in 11 countries. Through the use of larvicide

A larvicide (alternatively larvacide) is an insecticide that is specifically targeted against the larval life stage of an insect. Their most common use is against mosquitoes. Larvicides may be contact poisons, stomach poisons, growth regulators, o ...

spraying of fast-flowing rivers to control black fly populations, and from 1988 onwards, the use of ivermectin to treat infected people, the OCP eliminated onchocerciasis as a public health problem. The OCP, a joint effort of the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of h ...

, the World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Interna ...

, the United Nations Development Programme

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)french: Programme des Nations unies pour le développement, PNUD is a United Nations agency tasked with helping countries eliminate poverty and achieve sustainable economic growth and human dev ...

, and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)french: link=no, Organisation des Nations unies pour l'alimentation et l'agriculture; it, Organizzazione delle Nazioni Unite per l'Alimentazione e l'Agricoltura is an intern ...

, was considered to be a success, and came to an end in 2002. Continued monitoring ensures onchocerciasis cannot reinvade the area of the OCP.Effective prevention efforts include personal protection from black fly bites. Recommended protection measures include using insect repellents and wearing long sleeves and pants to eliminate exposed skin.Using insect repellent that contains N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) as well as clothing treated with permethrin, an insecticide, can provide additional protection from black fly bites.

Elimination

In 1995, the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC) began covering another 19 countries, mainly relying upon the use of the drug ivermectin. Its goal was to set up community-directed treatment with ivermectin for those at risk of infection. In these ways, transmission has declined. APOC closed in 2015 and aspects of its work taken over by the WHO Expanded Special Programme for the Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases (ESPEN). As in the Americas, the objective of ESPEN working with Government Health Ministries and partner NGDOs, is the elimination of transmission of onchocerciasis. This requires consistent annual treatment of 80% of the population in endemic areas for at least 10â12 years â the life span of the adult worm. No African country has so far verified elimination of onchocerciasis, but treatment has stopped in some areas (e.g. Nigeria), following epidemiological and entomological assessments that indicated that no ongoing transmission could be detected. In 2015, WHO facilitated the launch of an elimination program in Yemen which was subsequently put on hold due to conflict. In 1992, the Onchocerciasis Elimination Programme for the Americas, which also relies on ivermectin, was launched. On July 29, 2013, thePan American Health Organization

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) is an international public health agency working to improve the health and living standards of the people of the Americas. It is part of the United Nations system, serving as the Regional Office for ...

(PAHO) announced that after 16 years of efforts, Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North Americaânear Nicaragua's Caribbean coastâas well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

had become the first country in the world to eliminate onchocerciasis. In September 2015, the Onchocerciasis Elimination Program for the Americas announced that onchocerciasis only remained in a remote region on the border of Brazil and Venezuela. The area is home to the Yanomami

The Yanomami, also spelled YÄ

nomamö or Yanomama, are a group of approximately 35,000 indigenous people who live in some 200â250 villages in the Amazon rainforest on the border between Venezuela and Brazil.

Etymology

The ethnonym ''Yanomami ...

indigenous people. The first countries to receive verification of elimination were Colombia in 2013, Ecuador in 2014, Mexico in 2015 and Guatemala in 2016. The key factor in elimination is mass administration of the antiparasitic drug ivermectin

Ivermectin (, '' EYE-vÉr-MEK-tin'') is an antiparasitic drug. After its discovery in 1975, its first uses were in veterinary medicine to prevent and treat heartworm and acariasis. Approved for human use in 1987, today it is used to treat inf ...

. The initial projection was that the disease would be eliminated from remaining foci in the Americas by 2012.

No vaccine to prevent onchocerciasis infection in humans is available. A vaccine to prevent onchocerciasis infection for cattle is in phase three trials. Cattle injected with a modified and weakened form of ''O. ochengi'' larvae have developed very high levels of protection against infection. The findings suggest that it could be possible to develop a vaccine that protects people against river blindness using a similar approach. Unfortunately, a vaccine to protect humans is still many years off.

Treatment

In mass drug administration (MDA) programmes, the treatment for onchocerciasis is

In mass drug administration (MDA) programmes, the treatment for onchocerciasis is ivermectin

Ivermectin (, '' EYE-vÉr-MEK-tin'') is an antiparasitic drug. After its discovery in 1975, its first uses were in veterinary medicine to prevent and treat heartworm and acariasis. Approved for human use in 1987, today it is used to treat inf ...

(trade name: Mectizan); infected people can be treated with two doses of ivermectin, six months apart, repeated every three years. The drug paralyses and kills the microfilariae causing fever, itching, and possibly oedema, arthritis and lymphadenopathy. Intense skin itching is eventually relieved, and the progression towards blindness is halted. In addition, while the drug does not kill the adult worms, it does prevent them for a limited time from producing additional offspring. However the drug does not prevent transmission of Onchocerciasis.It however reduces morbidity and has shown promising results to elliminate in some endemic areas of Africa

Ivermectin treatment is particularly effective because it only needs to be taken once or twice a year, needs no refrigeration, and has a wide margin of safety, with the result that it has been widely given by minimally trained community health workers.

Antibiotics

For the treatment of individuals,doxycycline

Doxycycline is a broad-spectrum tetracycline class antibiotic used in the treatment of infections caused by bacteria and certain parasites. It is used to treat bacterial pneumonia, acne, chlamydia infections, Lyme disease, cholera, typhus, an ...

is used to kill the ''Wolbachia

''Wolbachia'' is a genus of intracellular bacteria that infects mainly arthropod species, including a high proportion of insects, and also some nematodes. It is one of the most common parasitic microbes, and is possibly the most common reproduct ...

'' bacteria that live in adult worms. This adjunct therapy has been shown to significantly lower microfilarial loads in the host, and may kill the adult worms, due to the symbiotic relationship between ''Wolbachia'' and the worm. In four separate trials over ten years with various dosing regimens of doxycycline for individualized treatment, doxycycline was found to be effective in sterilizing the female worms and reducing their numbers over a period of four to six weeks. Research on other antibiotics, such as rifampicin

Rifampicin, also known as rifampin, is an ansamycin antibiotic used to treat several types of bacterial infections, including tuberculosis (TB), mycobacterium avium complex, ''Mycobacterium avium'' complex, leprosy, and Legionnairesâ disease. ...

, has shown it to be effective in animal models at reducing ''Wolbachia'' both as an alternative and as an adjunct to doxycycline. However, doxycycline treatment requires daily dosing for at least four to six weeks, making it more difficult to administer in the affected areas.

Ivermectin

Ivermectin

Ivermectin (, '' EYE-vÉr-MEK-tin'') is an antiparasitic drug. After its discovery in 1975, its first uses were in veterinary medicine to prevent and treat heartworm and acariasis. Approved for human use in 1987, today it is used to treat inf ...

kills the parasite by interfering with the nervous system and muscle function, in particular, by enhancing inhibitory neurotransmission

Neurotransmission (Latin: ''transmissio'' "passage, crossing" from ''transmittere'' "send, let through") is the process by which signaling molecules called neurotransmitters are released by the axon terminal of a neuron (the presynaptic neuron), ...

. The drug binds to and activates glutamate-gated chloride channel

Chloride channels are a superfamily of poorly understood ion channels specific for chloride. These channels may conduct many different ions, but are named for chloride because its concentration ''in vivo'' is much higher than other anions. Severa ...

s. These channels, present in neurons

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoa. N ...

and myocytes

A muscle cell is also known as a myocyte when referring to either a cardiac muscle cell (cardiomyocyte), or a smooth muscle cell as these are both small cells. A skeletal muscle cell is long and threadlike with many nuclei and is called a muscl ...

, are not invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

-specific, but are protected in vertebrates

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

from the action of ivermectin by the bloodâbrain barrier

The bloodâbrain barrier (BBB) is a highly selective semipermeable membrane, semipermeable border of endothelium, endothelial cells that prevents solutes in the circulating blood from ''non-selectively'' crossing into the extracellular fluid of ...

. Ivermectin is thought to irreversibly activate these channel receptors in the worm, eventually causing an inhibitory postsynaptic potential

An inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) is a kind of synaptic potential that makes a postsynaptic neuron less likely to generate an action potential.Purves et al. Neuroscience. 4th ed. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates, Incorporated; 2008. ...

. The chance of a future action potential

An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific cell location rapidly rises and falls. This depolarization then causes adjacent locations to similarly depolarize. Action potentials occur in several types of animal cells, ...

occurring in synapses between neurons decreases and the nematodes experience flaccid paralysis

Flaccid paralysis is a neurological condition characterized by weakness or paralysis and reduced muscle tone without other obvious cause (e.g., trauma). This abnormal condition may be caused by disease or by trauma affecting the nerves associ ...

followed by death.

Ivermectin is directly effective against the larval stage microfilariae of ''O. volvulus''; they are paralyzed and can be killed by eosinophils

Eosinophils, sometimes called eosinophiles or, less commonly, acidophils, are a variety of white blood cells (WBCs) and one of the immune system components responsible for combating multicellular parasites and certain infections in vertebrates. A ...

and macrophages

Macrophages (abbreviated as M Ï, MΦ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''μακÏÏÏ'' (') = large, ''Ïαγεá¿Î½'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer ce ...

. It does not kill adult females (macrofilariae), but does cause them to cease releasing microfilariae, perhaps by paralyzing the reproductive tract. Ivermectin is very effective in reducing microfilarial load and reducing number of punctate opacities in individuals with onchocerciasis.

Moxidectin

After two decades of research, moxidectin was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for use in ages 12 and older. Ongoing studies are looking to identify doses that will be safe for children ages 4-11. The oral dosage for moxidectin in adults and children 12 and up is 8 mg in a single dose. Moxidectin has been found to more strongly suppress the ''O.'' ''volvulus'' microfilariae for longer than ivermectin treatments, with peak clearance of microfilariae in the skin at one month after treatment. At six months post treatment, many individuals treated with moxidectin have no detectable microfilariae present in their skin.Epidemiology

parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

in 2017; about 1.2 million of those had vision loss. As of 2017, about 99% of onchocerciasis cases occurred in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. Onchocerciasis is currently relatively common in 31 African countries, Yemen

Yemen (; ar, Ù±ÙÙÙÙÙ

ÙÙ, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi ArabiaâYemen border, north and ...

, and isolated regions of South America. Over 85 million people live in endemic areas, and half of these reside in Nigeria. Another 120 million people are at risk for contracting the disease. The ''Onchocerca volvulus'' main habitat is fast flowing rivers, Onchocerciasis is more commonly found along the large rivers in northern and central regions of the Africa. With a decrease in cases as you move farther away from those rivers. Multiple exposure to ''simulium blackflies'' raise the number of adult worms and microfilariae that are present in the host. Risk of contracting Onchocerciasis for causal travelers is low, since it often takes several exposures, while travelers that stay for longer visits such as missionaries or long-term volunteers have a greater risk of contracting Onchocerciasis. Onchocerciasis was eliminated in the northern focus in Chiapas

Chiapas (; Tzotzil language, Tzotzil and Tzeltal language, Tzeltal: ''Chyapas'' ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Chiapas ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Chiapas), is one of the states that make up the Political divisions of Mexico, ...

, Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, and the focus in Oaxaca

Oaxaca ( , also , , from nci, HuÄxyacac ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Oaxaca), is one of the 32 states that compose the political divisions of Mexico, Federative Entities of Mexico. It is ...

, Mexico, where ''Onchocerca volvulus'' existed, was determined, after several years of treatment with ivermectin

Ivermectin (, '' EYE-vÉr-MEK-tin'') is an antiparasitic drug. After its discovery in 1975, its first uses were in veterinary medicine to prevent and treat heartworm and acariasis. Approved for human use in 1987, today it is used to treat inf ...

, as free of the transmission of the parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

.In April of 2013, Colombia became the first country to achieve elimination of Onchocerciasis, verified by the World Health Organization. In the following three years, Ecuador and Guatemala, along with Mexico have been verified to have eliminated Onchocerciasis, with the use of ivermectin.

According to a 2002 WHO report, onchocerciasis has not caused a single death, but its global burden is 987,000 disability adjusted life years (DALYs). The severe pruritus

Itch (also known as pruritus) is a sensation that causes the desire or reflex to scratch. Itch has resisted many attempts to be classified as any one type of sensory experience. Itch has many similarities to pain, and while both are unpleasant ...

alone accounts for 60% of the DALYs. Infection reduces the host's immunity and resistance to other diseases, which results in an estimated reduction in life expectancy of 13 years.In 2017, the Global Burden of Disease study said that an estimated 220 million people needed preventive chemotherapy for onchocerciasis. Of those infected, 14.6 million had skin disease and 1.15 million were experiencing vision loss.

Onchocerciasis is the second leading cause of blindness from infectious causes. Main disease symptoms, such as blindness and itching, contribute to disease burden by limiting the infected individuals ability to live and work. Individuals most at risk are those who live or work in areas where ''simulium blackflies'' are most common, mostly near rivers and streams. Rural agricultural areas in sub-Saharan Africa see the most disease burden by blackfly bites. Onchocerciasis common to tropical environments, like that of sub-Saharan Africa, where more than 99% percent of infected individuals occupy the 31 countries. Onchocerciasis can be linked to impoverished remote areas, as residents who experience symptoms can no longer tend to land or navigate the area. Areas with high infection rates may experience up to one-third of residents affected by onchocerciasis symptoms. The age group most impacted by the disease are individuals age 61+ years.

History

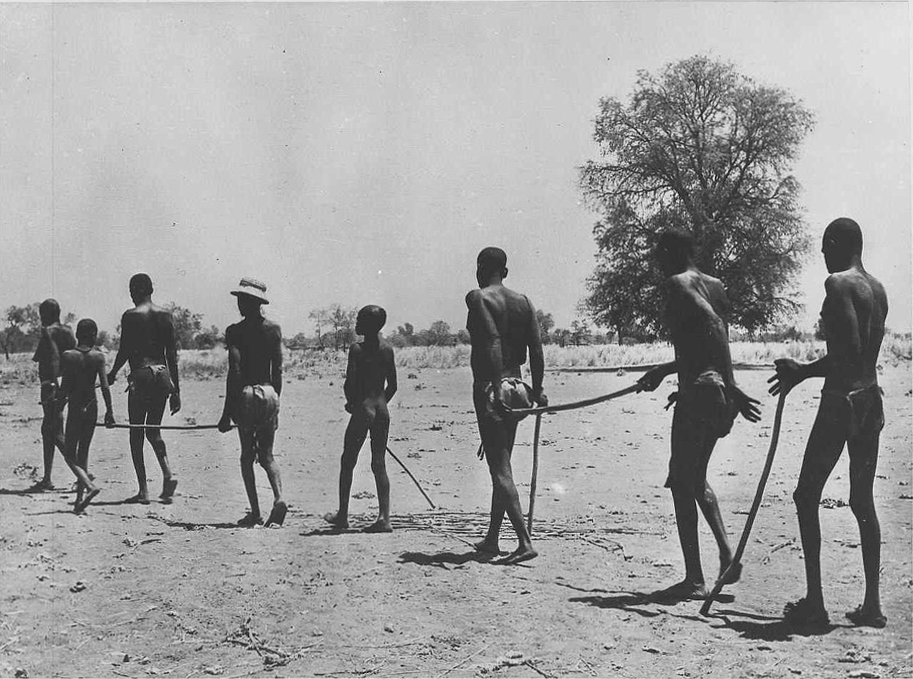

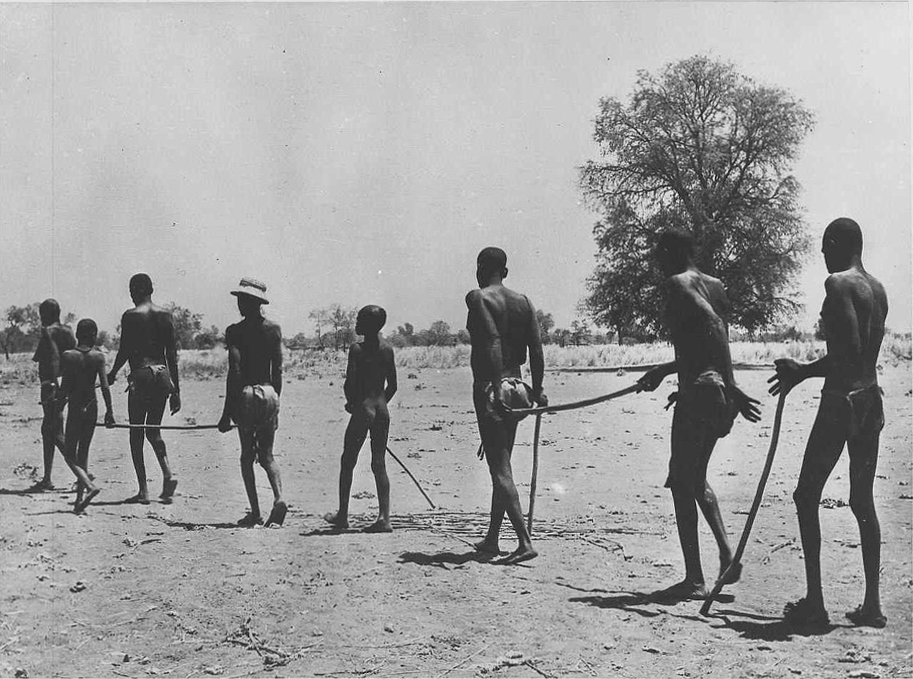

Onchocerca originated in Africa and was exported to the Americas by the slave trade, as part of theColumbian exchange

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, commodities, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the New World (the Americas) in ...

that introduced other old world diseases such as yellow fever into the New World. Findings of a phylogenetic study in the mid-90s are consistent with an introduction to the New World in this manner. DNA sequences of savannah and rainforest strains in Africa differ, while American strains are identical to savannah strains in western Africa. The microfilarial parasite that causes the disease was first identified in 1874 by an Irish naval surgeon, John O'Neill, who was seeking to identify the cause of a common skin disease along the west coast of Africa, known as "craw-craw". Rudolf Leuckart

Karl Georg Friedrich Rudolf Leuckart (7 October 1822 â 22 February 1898) was a German zoologist born in Helmstedt. He was a nephew to naturalist Friedrich Sigismund Leuckart (1794â1843).

Academic career

He earned his degree from the Uni ...

, a German zoologist, later examined specimens of the same filarial worm sent from Africa by a German missionary doctor in 1890 and named the organism ''Filaria volvulus''.

Rodolfo Robles and Rafael Pacheco in Guatemala first mentioned the ocular form of the disease in the Americas about 1915. They described a tropical worm infection with adult Onchocerca that included inflammation of the skin, especially the face ('erisipela de la costa'), and eyes. The disease, commonly called the "filarial blinding disease", and later referred to as "Robles disease", was common among coffee plantation workers. Manifestations included subcutaneous nodules, anterior eye lesions, and dermatitis. Robles sent specimens to Ãmile Brumpt

Alexandre Joseph Ãmile Brumpt (10 March 1877, in Paris â 8 July 1951) was a French parasitologist.

He studied zoology and parasitology in Paris, obtaining his degree in science in 1901, and his medical doctorate in 1906. In 1919 he succeeded ...

, a French parasitologist, who named it ''O. caecutiens'' in 1919, indicating the parasite caused blindness (Latin "caecus" meaning blind). The disease was also reported as being common in Mexico. By the early 1920s, it was generally agreed that the filaria in Africa and Central America were morphologically indistinguishable and the same as that described by O'Neill 50 years earlier.

Robles hypothesized that the vector of the disease was the day-biting black fly, ''Simulium''. Scottish physician Donald Blacklock of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

The Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) is a higher education institution with degree awarding powers and registered charity located in Liverpool, United Kingdom. Established in 1898, it was the first institution in the world dedicated ...

confirmed this mode of transmission in studies in Sierra Leone. Blacklock's experiments included the re-infection of Simulium flies exposed to portions of the skin of infected subjects on which nodules were present, which led to elucidation of the life cycle of the Onchocerca parasite. Blacklock and others could find no evidence of eye disease in Africa. Jean Hissette, a Belgian ophthalmologist, discovered in 1930 that the organism was the cause of a "river blindness" in the Belgian Congo. Some of the patients reported seeing tangled threads or worms in their vision, which were microfilariae moving freely in the aqueous humor of the anterior chamber of the eye. Blacklock and Strong had thought the African worm did not affect the eyes, but Hissette reported that 50% of patients with onchocerciasis near the Sankuru river in the Belgian Congo had eye disease and 20% were blind. Hisette Isolated the microfilariae from an enucleated eye and described the typical chorioretinal scarring, later called the "Hissette-Ridley fundus" after another ophthalmologist, Harold Ridley, who also made extensive observations on onchocerciasis patients in north west Ghana, publishing his findings in 1945. Ridley first postulated that the disease was brought by the slave trade. The international scientific community was initially skeptical of Hisette's findings, but they were confirmed by the Harvard African Expedition of 1934, led by Richard P. Strong, an American physician of tropical medicine.

Society and culture

Since 1987, ivermectin has been provided free of charge for use in humans byMerck

Merck refers primarily to the German Merck family and three companies founded by the family, including:

* the Merck Group, a German chemical, pharmaceutical and life sciences company founded in 1668

** Merck Serono (known as EMD Serono in the Unite ...

through the Mectizan donation program (MDP). The MDP works together with ministries of health and nongovernmental development organisations, such as the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of h ...

, to provide free ivermectin to those who need it in endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

areas. Due to the joint efforts of NGOs and WHO, onchocerciasis is no longer an obstacle in socio-economic development.

In 2015 William C. Campbell and Satoshi Åmura

is a Japanese biochemist. He is known for the discovery and development of hundreds of pharmaceuticals originally occurring in microorganisms. In 2015, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine jointly with William C. Campbell fo ...

were co-awarded half of that year's Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accord ...

for the discovery of the avermectin

The avermectins are a series of drugs and pesticides used to treat parasitic worms and insect pests. They are a group of 16-membered macrocyclic lactone derivatives with potent anthelmintic and insecticidal properties. These naturally occurring c ...

family of compounds, the forerunner of ivermectin. The latter has come to decrease the occurrence of lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis.

Uganda's government, working with the Carter Center

The Carter Center is a nongovernmental, not-for-profit organization founded in 1982 by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter. He and his wife Rosalynn Carter partnered with Emory University just after his defeat in the 1980 United States presidenti ...

river blindness program since 1996, switched strategies for distribution of Mectizan. The male-dominated volunteer distribution system had failed to take advantage of traditional kinship structures and roles. The program switched in 2014 from village health teams to community distributors, primarily selecting women with the goal of assuring that everyone in the circle of their family and friends received river blindness information and Mectizan

Ivermectin (, '' EYE-vÉr-MEK-tin'') is an antiparasitic drug. After its discovery in 1975, its first uses were in veterinary medicine to prevent and treat heartworm and acariasis. Approved for human use in 1987, today it is used to treat in ...

.

In 2021, Nigeria had the greatest prevalence of onchocerciasis infections globally, and attributed the infection to 30.2% of blindness cases in the country. A study from western Nigeria found that residents believed that the parasitic effects of the disease was necessary to stimulate fertility, and that the disease was thought to be carried by all residents.

Research

Animal models for the disease are somewhat limited, as the parasite only lives in primates, but there are close parallels. ''Litomosoides sigmodontis '', which will naturally infectcotton rat

A cotton rat is any member of the rodent genus ''Sigmodon''. Their name derives from their damaging effects on cotton as well as other plantation crops, such as sugarcane, corn, peanut and rice. Cotton rats have small ears and dark coats, and a ...

s, has been found to fully develop in BALB/c

BALB/c is an albino, laboratory-bred strain of the house mouse from which a number of common substrains are derived. Now over 200 generations from New York in 1920, BALB/c mice are distributed globally, and are among the most widely used inbred ...

mice. '' Onchocerca ochengi'', the closest relative of ''O. volvulus'', lives in intradermal cavities in cattle, and is also spread by black flies. Both systems are useful, but not exact, animal models.

A study of 2501 people in Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

showed the prevalence rate doubled between 2000 and 2005 despite treatment, suggesting the parasite is developing resistance to the drug. A clinical trial of another anti-parasitic agent, moxidectin

Moxidectin is an anthelmintic drug used in animals to prevent or control parasitic worms (helminths), such as heartworm and intestinal worms, in dogs, cats, horses, cattle and sheep. Moxidectin kills some of the most common internal and external ...

(manufactured by Wyeth

Wyeth, LLC was an American pharmaceutical company. The company was founded in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1860 as ''John Wyeth and Brother''. It was later known, in the early 1930s, as American Home Products, before being renamed to Wyeth in ...

), began on July 1, 2009NCT00790998

. (editorial) A

Cochrane review

Cochrane (previously known as the Cochrane Collaboration) is a British international charitable organisation formed to organise medical research findings to facilitate evidence-based choices about health interventions involving health professi ...

compared outcomes of people treated with ivermectin alone versus doxycycline plus ivermectin. While there were no differences in most vision-related outcomes between the two treatments, there was low quality evidence suggesting treatment with doxycycline plus ivermectin showed improvement in iridocyclitis

Uveitis () is inflammation of the uvea, the pigmented layer of the eye between the inner retina and the outer fibrous layer composed of the sclera and cornea. The uvea consists of the middle layer of pigmented vascular structures of the eye and i ...

and punctate keratitis, over those treated with ivermectin alone.

In 2017 the WHO set up the Onchocerciasis Technical Advisory Subgroup (OTS) to further research and establish areas that require drug administration. The OTS also identifies co-endemic areas with lymphatic filariasis to properly treat Onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis.

The WHO priorities research to achieve elimination of onchocerciasis. Research approaches include: improving outreach efforts to marginalized populations, expanding mapping of endemic areas of onchocerciasis, improve and standardize information on mass drug administration, develop diagnostic approaches, surveillance strategies, and therapeutic approaches

See also

*Carter Center

The Carter Center is a nongovernmental, not-for-profit organization founded in 1982 by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter. He and his wife Rosalynn Carter partnered with Emory University just after his defeat in the 1980 United States presidenti ...

River Blindness Program

* List of parasites (human)

Endoparasites Protozoan organisms

Helminths (worms)

Helminth organisms (also called helminths or intestinal worms) include:

Tapeworms

Flukes

Roundworms

Other organisms

Ectoparasites

References

{{Portal bar, Bio ...

* Neglected tropical diseases

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a diverse group of tropical disease, tropical infections that are common in low-income populations in Developing country, developing regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. They are caused by a variety ...

* Rodolfo Robles

Rodolfo Robles (1878â1939) was a Guatemalan physician and philanthropist. In 1915, he was the first to describe onchocerciasis in Latin America, which was known and widespread on the African continent and first described in 1890 by Sir Patr ...

* United Front Against Riverblindness

* Harold Ridley (ophthalmologist)

Sir Nicholas Harold Lloyd Ridley (10 July 1906 â 25 May 2001) was an English ophthalmologist who invented the intraocular lens and pioneered intraocular lens surgery for cataract patients.

Early years

Nicholas Harold Lloyd Ridley was born in ...

References

External links

CDC Parasites of public health concern

{{Authority control Spirurida Tropical diseases Helminthiases Infectious diseases with eradication efforts Parasitic infestations, stings, and bites of the skin Wikipedia medicine articles ready to translate Wikipedia infectious disease articles ready to translate